Fondazione Istituto Liszt

Via A. Righi n. 30, Bologna, ore 17

Hyo Soon Lee, soprano

Ida Zicari, pianoforte

Fondazione Istituto Liszt

Via A. Righi n. 30, Bologna, ore 17

Hyo Soon Lee, soprano

Ida Zicari, pianoforte

Fondazione Istituto Liszt

Via A. Righi n. 30, Bologna, ore 17

Zami Ravid, pianoforte

Fondazione Istituto Liszt onlus

Via A. Righi n. 30, Bologna, ore 17

Ludmilla Guilmault, pianoforte

Fondazione Istituto Liszt

Via A. Righi n. 30, Bologna, ore 17

Egidius Streiff, violino

Mariana Doughty, viola

Walter Grimmer, violoncello

Gregorio Nardi, pianoforte

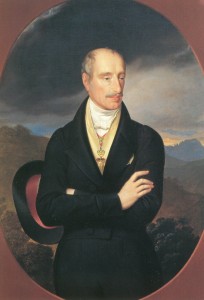

Leopold Kupelwieser, Ritratto di Ferdinando I d’Asburgo-Lorena, (Vienna, 19 aprile 1793 – Praga, 29 giugno 1875), imperatore d’Austria e re d’Ungheria (comeFerdinando V) dal 2 marzo 1835 al 2 dicembre 1848

Johann Nepomuk Ender, Ritratto Maria Anna Carolina Pia di Savoia (Roma, 19 settembre 1803 – Praga, 4 maggio 1884), imperatrice d’Austria

Joseph Karl Stieler, Ritratto di Teresa di Sassonia-Hildburghausen nel giorno dell’incoronazione. Teresa di Sassonia (Seidingstadt, 8 luglio 1792 – Monaco di Baviera, 26 ottobre 1854) fu regina di Baviera come moglie del re Ludovico I

François Gérard, Ritratto di Maria Luisa imperatrice dei francesi, 1810. Maria Luigia di Parma (Vienna, 12 dicembre 1791 – Parma, 17 dicembre 1847), già imperatrice consorte dei francesi dal 1810 al 1814 come moglie di Napoleone I, fu duchessa regnante di Parma, Piacenza e Guastalla dal 1814 al 1847

Anonimo, Ritratto di Ranieri Giuseppe Giovanni Michele Francesco Geronimo d’Asburgo, arciduca d’Austria (Pisa, 30 settembre 1783– Bolzano, 16 gennaio 1853), viceré del Lombardo-Veneto

We publish here the manuscript of All’amica lontana, pensiero patetico op. 16 by Adolfo Fumagalli kept in the archive of the Fondazione Istituto Liszt. The piece was composed in March 1848 in Turin, where the pianist was living for a while in Maestro Fabbrica’s house, after finishing his studies at the Milan Conservatory the year before. At the end of March of the same year he was back in Milan, and in August he decided to go once again to Turin and then to Paris, where he arrived only one year later, in March 1849. There, after a very hard start, he was finally acclaimed as «the Paganini of the piano» some years after. In this small salon piece we find all of Fumagalli’s technical skills, including a clever way to avoid the risk of repetitions in the ABA form basically constructed of phrases of 4 measures long.

The paper presents an unpublished letter of Liszt to his best student, Sophie Menter, probably dating back to January 16, 1881, and reconstructs the context. In the paper are cited the well-known librarian and musicologist Francesco Florimo, Liberato Aureli, Liszt’s waiter, and Maria Giuli, another pupil of Liszt and niece of Giovanni Pacini, about whom the author has already published unknown documents in this same journal (2013).

In his account of the «second age of the symphony» James Hepokoski (2002) classifies the orchestral compositions of British composers Charles Villiers Stanford and Hubert Parry as «nationalistic» works that exoticise, but otherwise uphold, Austro-German models. This perpetuates the traditional view of a nineteenth-century British symphonic tradition failing to uphold the criterion of originality central to nationalism and to the symphony’s «second age» generally. Closer scrutiny of the symphonies of Stanford and Parry reveals complex syntheses of traditionalistic and modernistic strains: both composers negotiated the conflicting imperatives of experimentation, originality and linguistic approachability that confronted the full range of symphonists of all nations – including Franz Liszt. Several of Stanford’s symphonies contain programmatic elements and inter-movemental, “cyclical” processes that evoke the compositions of Liszt. The limited and controversial dissemination of Liszt’s orchestral music in later nineteenth-century Britain, coupled with blatant differences in stylistic orientation, obscures any path of influence running directly from Liszt to Stanford. Nonetheless, comparisons between Liszt and Stanford’s Fourth Symphony (originally prefaced by lines from Goethe’s Faust) and Sixth Symphony (a response to paintings and sculptures by George Frederick Watts) indicate that “modern” techniques inhered in works traditionally seen in a “reactionary” light. Such comparisons also point towards Liszt’s partial acceptance of traditional structuring principles, even in such apparently iconoclastic works as the Faust Symphony.

Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 17 is a puzzling miniature written towards the end of the composer’s life: much of its idiomatic material, as well as the traditional slow-fast pairing, is represented in a highly abstract way that defies generic listening. The work’s largely euphonious harmony and ambiguous genre perhaps explain why it has not fitted well into received narratives and discourses on Liszt’s late music: but it is precisely its harmonic and anti-generic aspects that deserve closer attention.

This article therefore begins by contextualizing the work as a Rhapsody and then proceeds to examine salient ways in which Liszt creates a quasi-“distancing effect” that denies listeners the pleasure of immersing themselves in exoticism, nationalism and virtuosity. The second part looks more closely at how this work avoids the affirmative affective route expected in a Rhapsody, and instead continuously transforms three idiomatic (and extremely simple) motifs in order to create something closer to a dreamlike psychological drama or even a nightmare – unlike any other Rhapsody ending in a fast tempo.

The final part examines the role tonality plays in creating this dream world; more specifically, Liszt’s cryptic key signatures and note spellings, some of which seem to go against a more intuitive perception of harmony. Two contradictory readings, employing both Neo-Riemannian and prolongational perspectives, highlight this riddle. The first demonstrates that, notwithstanding Liszt’s D minor-to-major key signatures, the work can be heard as tonally coherent when B-flat is considered to be the central sonority against a largely chromatic background. The second reading takes Liszt’s key signatures and spellings seriously and presents a tonal process that is only a fragment of a greater, imperceptible whole, much like other elements in this fascinating work.

The output of Antonio Fanna, important pianist, teacher and music promoter in Venice in the early nineteenth century, effectively sums up, as a first example in Italy, the instrumental meeting between Classicism and Romanticism. Highly esteemed by leading musicians and performers of his time, Liszt in particular, Fanna composed works which, although marked by the brilliant style and suggestions of melodrama, pursue the demands of art, revealing the composer as one of the most interesting in the development of taste and the perfection of technique. His story intertwines with the Venetian culture and patriotic fervors of Daniele Manin, with whom he associated.